The Birth of the Wellington Film Festival

The Wellington Film Festival was born out of the film society movement.

In the same year that I was elected president of the Wellington Film Society I was appointed programmer for New Zealand’s 50 film societies. It was 1970 and I was a television journalist with a yen to be entrepreneurial and plenty of spare time for extra activities. For the film societies, I had to organise an annual season of films, all to be screened from 16mm prints. I discovered that we could buy the rights for critically-acclaimed new titles which were being released in cinemas in London and New York but weren’t being seen in New Zealand because local cinema owners wouldn’t show them. Many more titles were available only on 35mm prints. But in those days film societies didn’t have access to 35mm projection.

Early in 1972, after a couple of years of being frustrated because there were so many unseen titles which film societies couldn’t show on their 16mm projectors, I flew to Sydney to learn about the mysteries of film festivals from David Stratton who’d been running the Sydney Film Festival since 1966. He was generous with his advice about starting a film festival. And he surprised me by saying that some of the 35mm prints from his programme could be available for us to show in Wellington - if only we had a festival. So I came home and proposed the idea at the next meeting of the Wellington Film Society committee. They agreed that we would launch an annual film festival, to premiere new films of quality which would otherwise not be available for local audiences to see.

New Zealand’s film distributors told us the idea was useless. They were smugly confident that Wellington filmgoers wanted movies only from the mainstream American and British suppliers. Wellington cinema managers had no faith in the idea either. They all said no to my request – except for Merv and Carol Kisby who were running the Paramount. They agreed to give us a chance. So we booked seven days in July.

For that First Wellington Film Festival, we advertised the premieres of seven new features – one per day. The festival included new features by Louis Malle, Eric Rohmer, Gillo Pontecorvo, Mauro Bolognini and Luis Bunuel. It’s amazing to recall that in those days the established distribution systems had no interest in these films. Audiences did, of course. We sold 5000 tickets. The second festival expanded cautiously to 12 titles. In 1974 we showed sixteen, and our third-year audience rose to 11,000. Film society committee member David Lindsay created our first souvenir programme book. And we showed our first New Zealand film, a short documentary about Ralph Hotere directed at the National Film Unit by Sam Pillsbury. A year later, in a programme of 23 titles (which attracted an audience of 14,000), we screened our first New Zealand feature – Test Pictures. Geoff Steven, director of Alternative Cinema, had shot the film with Philip Dadson and Denis Taylor two years earlier, but they’d exhausted their $14,000 budget without being able to finish the film. The film society bravely agreed to pay $500 so that a screening print could be made. The result was our first world premiere.

We invited MPs to be festival guests, in an attempt to help the campaign to get state support for filmmaking in New Zealand which had been launched in 1970 in a bracing speech by pioneer Wellington producer John O’Shea. But it didn’t help the cause. Our political guests couldn’t find any connection between familiar Hollywood genres and the long uninterrupted takes of the local production. Auckland university film lecturer Roger Horrocks wrote in the student newspaper Craccum: “It is so uncompromising – so foolhardy if you will – that I don’t think the group has much chance of retrieving their money.”

In the same programme, the film festival introduced the documentary work of Alister Barry. His Mururoa 73 was about the French navy capturing a boat sent by the New Zealand government to protest against nuclear testing in the Pacific. The subject may have further contributed to the discomfort of some of our official guests.

We didn’t find another New Zealand feature for the film festival till 1977 when we screened Landfall, written and directed (also at the National Film Unit) by Paul Maunder. It had been made as a TV movie and had won a prize in Iran, but the Broadcasting Corporation didn’t want to show it. They were even reluctant to allow us to screen at the film festival. Negotiations took 12 months.

One of the actors in Landfall was a young NFU director named Sam Neill. Another was film society member Jonathan Dennis, who had become a regular film festival audience member - he would always sit in the centre of the front row. An outspoken critic, he reviewed us on the 2YC Critics programme in 1976: “This year was a good year. Only seven films were inconsequential and pretty execrable, three unsatisfactory or merely feeble, eight mildly interesting, eight worth seeing and four were superior achievements. There was actually an abundance of things worth seeing.” In 1981 he would become the founding director and sole staff member of the New Zealand Film Archive and the festival would begin a relationship which resulted in some memorable retrospective selections.

Censorship was an annual embarrassment for the first five Wellington Film Festivals. In 1975, director Michael Thornhill was a festival guest for the premiere of his discreet new Australian feature film Between Wars. The word “fuck” was used several times on the soundtrack. “Indecent,” pronounced censor Doug McIntosh, who said he had to cut the print because such a word could not be allowed to be heard in a public place. “But it’s not our print,” I told him. “You can’t cut a print which we don’t own.” To my surprise, he agreed to stick black tape over the soundtrack so the words wouldn’t be heard and the print wouldn’t be butchered. When the director arrived he was incensed that his freedom of expression had been interfered with, specially as the film had been shown in Australia without cuts. He climbed the shaky ladder to the Paramount projection box and peeled the censor’s black tape off the film. When he introduced the film, he announced what he had done. The audience cheered. The four-letter words were heard. The world didn’t end. But the censor said he would do us no more favours. It was inevitable, therefore, that we became involved in the fight for censorship reform. “We continue to be hampered by a law written sixty years ago, which still allows cuts to be made before Film Festival audiences can see a work of art,” I wrote.

Lawyer David Gascoigne agreed to help us seek changes in the law. We went to meetings of a parliamentary select committee and watched the morals campaigner Patricia Bartlett hand out copies of Playboy magazine from a suitcase. Then David proposed that a new censorship law could require the censor to consider the nature of the film as a whole, as well as the nature of the audience. After the law was passed in 1977, cuts became a thing of the past for the film festival (and for film societies) if not for everyday filmgoers. Certificates saying “only for film festival audiences” were a sure way of attracting full houses.

Audiences grew and grew. The fifth film festival sold five times as many tickets as the first event and showed four times as many titles. Each year was the biggest programme ever. How did a volunteer organization cope with an event that was growing so fast? “We remain, as always, a predominantly volunteer organization running an ever-expanding cultural event on a shoestring budget with no official support or subsidy,” I had written, somewhat grumpily, in 1976. We showed new films by the greatest contemporary directors. Werner Herzog, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Wim Wenders, Volker Schlondorff, Kevin Brownlow, King Hu, Dusan Makavejev, Miklos Jansco, Andrzej Wajda, Robert Bresson, Eric Rohmer, Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Alain Resnais, Marguerite Duras, Agnes Varda, Bertrand Tavernier, Carlos Saura, Martin Scorsese, Frederick Wiseman, John Huston, the Taviani Brothers, Nikita Mikhalkov, Andrei Tarkovsky. Without the film festival, most of the films would have stayed unseen in Wellington.

We championed the work of New Zealand directors too, whenever it was possible. The Seventh Wellington Film Festival premiered Vincent Ward’s A State of Siege. Later festivals introduced the first work of hometown directors including Gaylene Preston and Peter Jackson, among others, with standing ovations.

Reviewing the fortieth anniversary of the Auckland Film Festival (which began three years before Wellington) Roger Horrocks has written that the event was one of the catalysts for the emergence of a local film industry. All the future film directors were regular Festival-goers, and in later years some said that the annual exposure to so many different kinds of film, some from countries as small as ours, had helped to inspire their own early efforts. It was the same in Wellington.

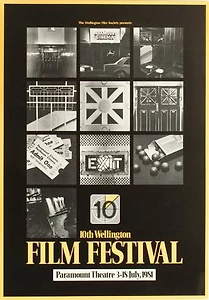

The tenth Wellington Film Festival offered a programme of 57 titles. It was the last that I directed. By then, I’d become marketing director at the newly-established Film Commission. At last New Zealand feature films were being made every year. And my job of selling them to the world didn’t leave me any more spare time. In the tenth programme I wrote:

“Ten years ago when we began, we didn’t know whether our hopes and interests would be shared by enough Wellingtonians to enable us to continue. Today, we are encouraged by the fact that a majority of our main features are sellouts, and the Wellington Film Festival has become an established feature of Wellington life, one which enables thousands of people to see some of the world’s best new films.

“We have done this entirely by voluntary effort – the film festival, unlike most other similar events, has had no financial support from any civic or national body as it has expanded to its present substantial size. There has however been a decade of generous support from many individuals, both in terms of time given to assist with the complex organizationals demands, and also in terms of the generous provision of prints which comes from many parts of the world.

The Wellington Film Festival has also helped to change attitudes towards films in local cinemas. A number of the films first championed by us have gone on to lengthy commercial runs. I don’t believe this would have happened had not the festival first had the courage to bring them here.”

Unpaid volunteers would remain a mainstay of the festival, but its early growth – which was paralleled by the growth of film society membership numbers - led to pressure to employ staff. Rosemary Hope, who was honorary secretary of the Wellington Film Festival, became our first paid employee when membership of the Wellington Film Society grew to more than 2000 and the voluntary membership secretary resigned when piles of cheques became too much for her to handle on her kitchen table. As well as being the administrator of the Wellington Film Society and of the national federation of film societies, Rosemary spent four months every year administering the film festival. Bill Gosden, recently arrived in town from Otago University, took over when she departed for a new life in England. Then he was ready and willing to become the festival’s first full-time professional director when the Film Commission took over my life.

The growth during his 30 years of stewardship has been extraordinary. Who would have believed that the festival would outgrow the Paramount and move into the Embassy? Who would have believed that the festival would outgrow the Embassy and have to return to the Paramount as a second venue? Who would have believed that as audiences grew and grew, the festival would occupy four or even five different venues in the city? Who would have forecast that a film festival in Wellington would attract an annual audience as high as 70,000? Bill’s talent as a festival director has not only driven the continuing expansion of the Wellington Film Festival (and the national event of which it is a key part, second only to Auckland in numbers) but also has given it a world-wide reputation for excellence of which we can all be proud, at the same time as we continue to take pleasure in trying to choose what to see in every annual programme.

by Lindsay Shelton

Director of the Wellington Film Festival from 1972 to 1981