Screened as part of NZIFF 2001

Errol Morris’ First Person 2000

We wait 20 years for Errol Morris' first six documentaries, then along come the next eleven all at once. This embarrassment of riches is due to the miracle of television, or more precisely executives of US television network Bravo, who must have figured that Errol was fast, cheap, but not completely out of control.

Although the individual half-hour films that comprise the First Person series are necessarily less ornate than Morris' features (think Mr Death if Fred Leuchter was a designer of execution equipment and no more), they bounce off one another in fascinating ways, comprising a collage of millennial anxiety – about death, about debt, about the unknown. The uncanny alchemic resonances that one found within Fast, Cheap and Out of Control in this context become part of the bigger picture.

Virtually all of the films are built around a single talking head interview, enlivened by Morris' characteristic inserts: illustrations, reconstructions, hoary found footage. He effortlessly adapts his style to the small screen not by compromise or curtailment but simply by finding smaller subjects.

In the later episodes, Morris' signature apparatus the Interrotron (a device which enables the interviewee to enjoy direct eye contact with both interlocutor and audience) is supplanted by the Megatron, which employs up to 20 cameras in a similar arrangement. The consequent visual fragmentation of an uninterrupted monologue from one of the filmmaker's gallery of eccentrics – who may be informing us how to lose one's tail in Moscow, which bleach is best for blood, or why a plaster cast of Chang and Eng is such a treasure – is powerfully disorienting: a televisual cliché given surprising new life, 60 Minutes live from Mars.

Some of these stories have had long gestations. Several of them, formerly known as the Interrotron Stories, were filmed years before the First Person series was aired; The Parrot was produced as a pilot for the Fox network, who rejected it as 'more than 20 percent new' (people really, really like 'new', they explained, but only in non-toxic doses).

More than just a clearing of his files, this series may be Morris' most personal work to date. Not only is there more of Errol Morris himself in these films than ever before – in the form of his questioning voice and disembodied televised head (Andrew Cappoccia, Mr. Debt, is the most aggressive in dragging Morris into his film) – but the interests and obsessions of his subjects are uncommonly close to his own. Gary Greenberg's strange relationship with the Unabomber, for instance, discreetly parallels Morris' with Ed Gein, and the leitmotifs of First Person are those found throughout his oeuvre: crime and its consequences, the fringes of science, necrogenic economics. — Andrew Langridge

First Person One

Stairway to Heaven

Photography: Ian Kincaid, Tom Krueger

Editor: Schuyler Cayton

Production designer: Ted Bafaloukos

Music: Caleb Sampson

'What would it be like if I actually were a cow?' — Temple Grandin

Temple Grandin thinks in images. Diagnosed autistic, this anthropologist feels profoundly attached to the animal world, and has used her capacity for empathy to develop a more humane slaughterhouse, in which fear and panic is replaced by calm and reassurance – right up until the bolt gun strikes.

Eyeball to Eyeball

Photography: Martin B. Albert

Editor: Doug Abel

Sound: Steve Bores

Music: John Kusiak

'I guess a lot of people would think: who could love a squid?' — Clyde Roper

Clyde Roper would like nothing better than to be eyeball to eyeball with Architeuthis, and what an eyeball that would be – big as a human head. To date, no-one has ever seen the monster in its natural habitat, and Clyde would love to be first. In fact, Clyde would be happy to have just 15 seconds to observe the giant squid: the 15 seconds before the 60-foot creature crushes his bathysphere and devours him. In this film Morris conveys something oddly inspirational about the extremities of scientific obsession.

I Dismember Mama

Photography: Ian Kincaid

Editors: Shondra Burke, Karen Schmeer

Production designer: Ted Bafaloukos

Music: Caleb Sampson

'People often see Dr. Frankenstein as some horror story. I just think he's misunderstood.' — Saul Kent

If you're a pioneer of cryonics, and death comes knocking, hide in the fridge. Bearing in mind Norman Bates's aphorism, 'a boy's best friend is his mother,' Saul Kent had Dora Kent freeze-dried for posterity, preserving her head for that happy future thaw when mother and son might be reunited.

Little Gray Man

Photography: Martin B. Albert

Editor: Julianna Parroni

Sound: Steve Bores

Music: John Kusiak

'The really good spies don't need disguises. They're just… uninteresting.' — Antonio Mendez

Antonio Mendez, former master of disguise, shares some of the tricks of his trade: the commandments of espionage, how to have fun while being tortured, how to disappear completely. But what happens to one's identity if it is permanently suppressed? Mendez unconsciously avoids using the first person when answering Morris' questions but, when confronted, acknowledges the risk of losing one's true self in a wilderness of mirrors.

First Person Two

In the Kingdom of the Unabomber

Photography: Martin B. Albert

Editor: Doug Abel

Sound: Steve Bores

Music: John Kusiak

'He takes a shortcut to getting his name out there and I just sort of follow in his wake. You know, it's like chasing an ambulance…' — Gary Greenberg

Not everyone would be happy to get a letter from the Unabomber, but Gary Greenberg was thrilled – though he got his wife to open it. And so begins the psychologist's subtle slide into a mire of moral relativity, as he debates metaphysics with a mass murderer and becomes inveigled in peculiar, mutually manipulative relationships with Ted Kaczynski and other of his courtiers…

The Killer Inside Me

Photography: Ian Kincaid

Editor: Karen Schmeer

Production designer: Ted Bafaloukos

Music: Caleb Sampson

'Evil is real, and evil walks the earth like a natural man.' — Sondra London

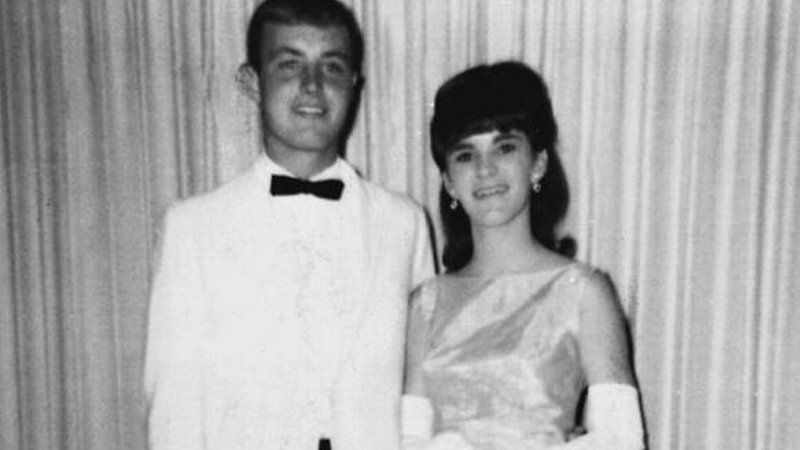

Seriality comes in many forms. Having split up with her childhood sweetheart – twice – because of his unpleasant compulsion to kill women, Sondra London then took up with Danny Rollins, serial killer number two. He serenades her; she goes all gooey. Is this passion or pathological self-deception?

Mr. Debt

Photography: Martin B. Albert

Editor: Chyld King

Sound: Steve Bores

Music: John Kusiak

'You can't make 'em feel guilty, but if you sue 'em, you can make 'em understand.' — Andrew Cappoccia

Andrew Cappoccia spends his days dragging credit card companies through the courts, with considerable success. These companies are expert in utilising the dream of unlimited credit to mask the nightmare of fathomless debt. Cappoccia offers shrewd analyses of their diverse scams and exposes the invidious position of any cardholder who tries to fight them. If you own a credit card, this horror film is made especially for you.

The Parrot

Photography: Christoph Lazenburg

Editor: Shondra Burke

Production designer: Ted Bafaloukos

Music: Caleb Sampson

'Richard! – No! No! No!' — Max

This terrific whodunnit, its plot as pulpy as the trashiest TV movie, is the most conventionally structured of the series (an array of interviews attempts to uncover the truth of an Event), but its content is perhaps the most eccentric of any of them. Who killed Jane Gill? Morris invites viewers to weigh the testimony of the disgruntled ex-fiancée, the devoted girlfriend and the only eye-witness to the killing: Jane's grey parrot (or red herring?) Max. In so doing he subtly casts aspersions on the reliability of First Person's other witnesses. Is the appeal of a good story – or several – enough to make the truth irrecoverable?

First Person Three

Smiling in a Jar

Photography: Martin B. Albert

Editor: Juliana Parroni

Sound: Steve Bores

Music: John Kusiak

'Some of the names I know, some I don't. But they're all human beings – or parts thereof.' — Gretchen Worden

The Mütter Museum is a macabre collection of anatomical specimens dating back to the nineteenth century, and Gretchen Worden is its deadpan, self-deprecating custodian. Among her treasures are pickled heads, the skeletons of dwarfs, tumours of the rich and famous. Her appreciation of the beauty and fascination of these human remains as objects sits, somewhat uneasily, alongside her respect for the men and women they represent.

The Stalker

Photography: Walt Lloyd

Editor: Shondra Burke

Production designer: Ted Bafaloukos

Music: Caleb Sampson

'The devil has a name; I have nothing.' — Bill Kinsley

When misanthropic postal worker Thomas McIlvane opened fire on his colleagues, his boss escaped unscathed, only to be cut down in the crossfire of recriminations that followed the bloodbath. Here Morris provocatively flaunts the central conceit of the series. Kinsley is featured not for what he has done, but for what has been done to him. Being less subject than object, there's a keen sense of other perspectives, other voices that Morris' format excludes. This crisis of subjectivity is pushed even further in The Parrot.

You're Soaking in It

Photography: Martin B. Albert

Editor: Chyld King

Sound: Steve Bores

Music: John Kusiak

'Sometimes nobody cares – except me.' — Joan Dougherty

When her stepson was shot in 1982, there was nobody to clean up the mess, so Joan Dougherty mucked in and incidentally discovered one of the most unlikely niche markets of all. Now this ex-hairdresser has a new profession: death-scene cleaner. Dougherty is called upon to sort out the leftovers of overlooked lives. When the body of a reclusive old man is found weeks after his death, it's Joan's job to make the apartment rentable and dispose of a lifetime's worth of memories.