Screened as part of NZIFF 2001

Blossoms of Fire 2000

Ramo del fuego

When the French edition of Elle published an article about the women of Juchitán, Mexico, they announced that these mujeres rule over their men and the Spice Girls brand of girl power has spread to indigenous Mexico. But rather than trade high fives and you-go-girls, the women in question were less than pleased. Their response: don’t plug us into your first-world battle of the sexes… Luckily, the American directors of the documentary Blossoms of Fire capture the nuances of gender relations that middle-school-mentality Elle can’t grasp.

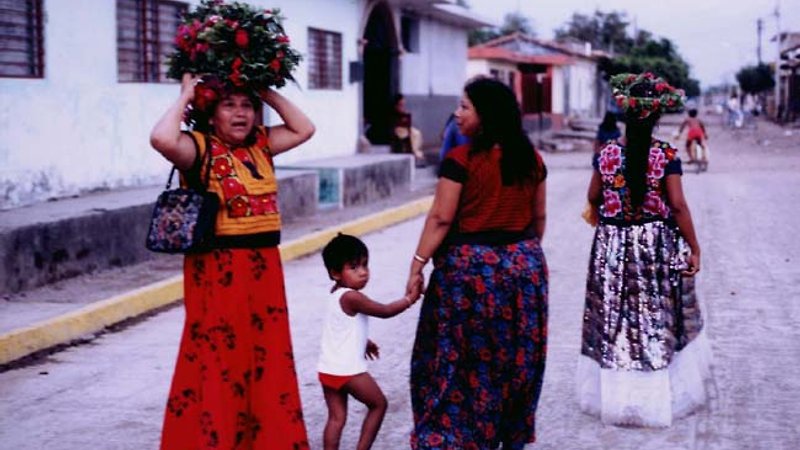

The idea of a gender war is as foreign to Juchitán as Taco Bell. When asked about ‘the matriarchy,’ the women in the film choose their words carefully, saying (with a wry smile), ‘We don’t dominate, but we do administrate.’ The palpable self-confidence and independence of Juchitán women does not preclude cooperation with and respect for men. The film shows that this balance is at least partially rooted in economics – both women and men possess marketable skills and a hard-wired work ethic. Juchitán’s food and craft market, the center of economic life, is run by entrepreneurial women, many of whom have shown up at four in the morning every day for the last 25 years, developing a deep female camaraderie and support network as well as earning a living.

The status of women is a sign of a larger progressive personal politics in Juchitán, the first town to challenge Mexico’s dominant political party, the PRI. Discussing the tolerance regarding homosexuality, a lesbian noted that gay people in Juchitán don’t have a ‘realization’ that they are gay at age 17 or 25 or 35; that it is part of who people are their whole lives. The most crowd-pleasing moment of the film comes when a gay man tells the camera, ‘It is the gay men that stay home and take care of their mothers. The straight ones go and get married and have their own families.’ In Juchitán, a mother thinks, ‘If only I could be so lucky as to have a homosexual in my family!’

So is Juchitán some sort of enlightened utopia? When the directors of Blossoms of Fire elicit intimate interviews, document the area’s physical beauty, weave history into the present, and show Juchitán as a place where respect for others is a way of life, it’s tough to think otherwise. — Carson Brown, Fabula, 7/00